It’s interesting the way some successful artists reflect upon their lives. Internationally renowned artist Nan Goldin had long berated herself for years of addiction, especially to opiates. “Every morning I’d wake up in hell, waking up to self-condemnation. And then I’m taking two hours to get up because it’s so awful.” These comments were made during her session with celebrated physician and addiction therapist Dr Gabor Mate.

Buzz and Nan at the Afterhours, New York City, 1980

Reading of her sessions with Mate, you’d swear she’d never been a ‘creative dynamo’ who has produced a vast body of powerful and distinctive art, exhibiting internationally to great acclaim. “I’ve missed years of my life, I don’t have many more years to go. I’ve spent most of my life addicted to drugs and as a result, know nothing. My knowledge is very limited, I didn’t look in the mirror and deal with myself. So much has been lost.” She went on to say that she feels worthless and defective.

Rise and Monty Kissing, New York City, 1980

She was born Nancy Goldin into a middle class Jewish family in Boston in 1953. She is the youngest of four children and was particularly close to her sister, Barbara, who from an early age rebelled against middle class American life. This, in a climate of silence and denial. Barbara spent time in institutions before committing suicide at the age of 18, when Nan was 11. Speaking of Barbara, Goldin argues that in the early sixties, women who were sexual and angry were considered dangerous and outside the range of acceptable behavior. She described her sister as being born at the wrong time with no tribe, no other people like her. It’s argued that the gritty realism of Goldin’s work, the desire to tell it as it is has its roots in these early childhood experiences.

Trixie on the Cot, New York City, 1979

Goldin decided at an early age she would record her life and experiences “that no one could rewrite or deny”. One of her closest friends was the photographer David Wojnarowicz (see my blog dated 8 May, 2020), and like him, she used photography as an act of resistance. She moved to New York in 1979 and began producing photographs of those in her immediate environment. Her most celebrated body of work is “Ballad of Sexual Dependency”, a project which began in the early 1980’s.

In her critique of an exhibition based around ‘Ballad’, held at MOMA in 2016, Tasya Kudryk argues that Goldin had an intense relationship with her subjects whom she described as her family. “The artist’s work captures an essential element of humanity that is transcendent of all struggles: the need to connect.” Goldin claims it’s impossible to capture the essence of a person in a single image, instead she aims to “capture the swirl of identities over time.” Her images include relationships in transition, of couples drifting together and then apart. She doesn’t shy away from depicting violence, such as her self portrait showing the aftermath of a battering she received from a boyfriend that almost blinded her. The message seemed to be that while sex can be a cure for isolation, it can be a source of alienation.

Nan, One Month After Being Battered, 1984

Ballad of Sexual Dependency has been described as a deeply personal visual diary narrating the struggle for intimacy and understanding between her friends, family and lovers. The setting is mainly the hard-drugs subculture of New York’s lower east side. (Interestingly, some former inhabitants lament the gentrification of the area that has taken place recently.) Goldin wants her work not to be seen in the context of observer, but as participant. “Ballad” is now regarded as a contemporary classic, raising awareness around issues such as homosexuality and AIDS. “Goldin's open, frank style of narration and dense colour make the viewer go beyond the surface of the photograph to encounter a subterranean intensity “- Kudryk. Yet permeating these images is a sense of loss. "I used to think that I could never lose anyone if I photographed them enough. In fact, my pictures show me how much I’ve lost." - Goldin.

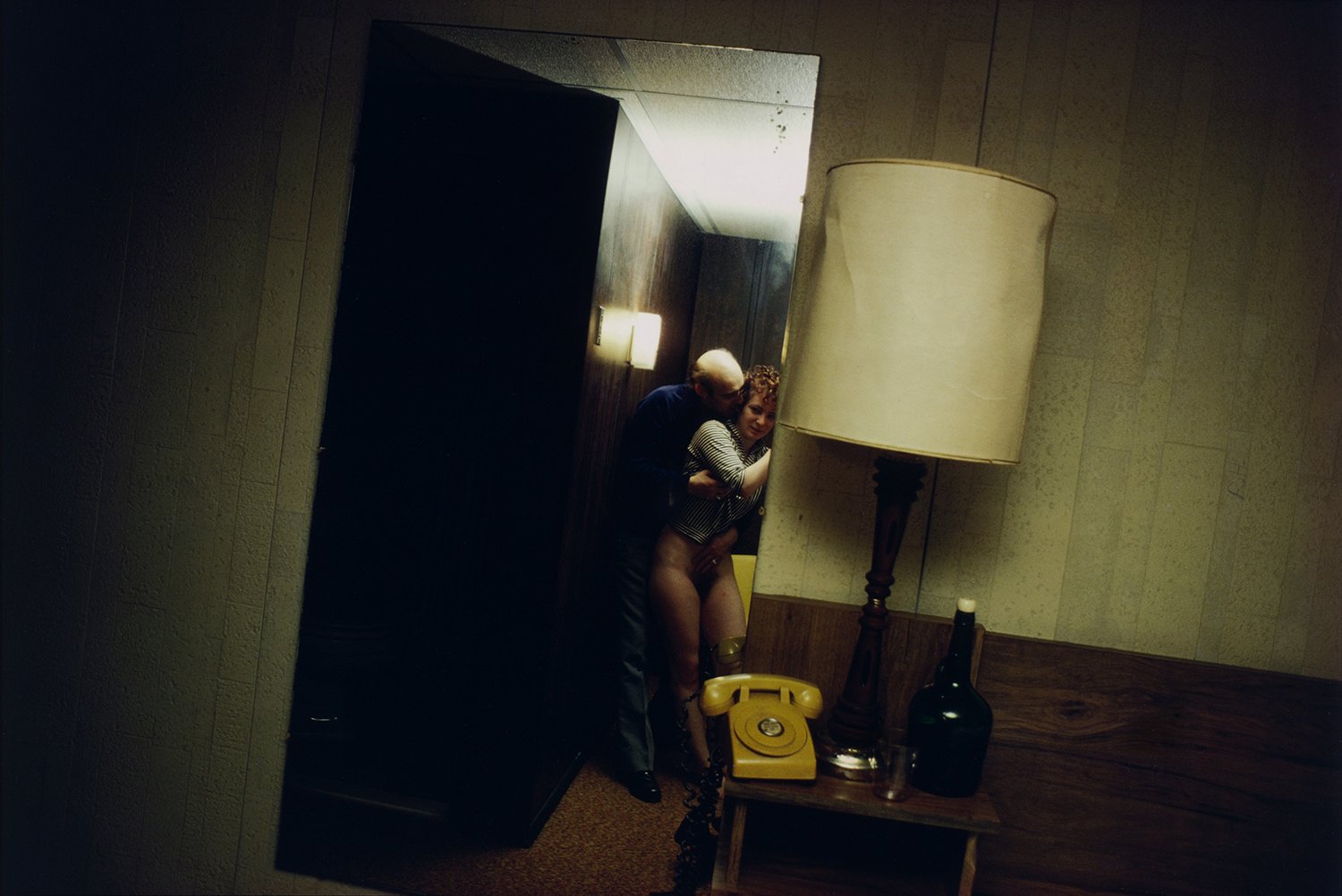

Nan and Dickie in the York Motel, New Jersey, 1980

Goldin acknowledges that her escape into substance use rescued her when she resorted to it at age 18, when going through a painful time in her life. “Literally, addiction saved my life”, she told Mate. Otherwise, she may have been driven to suicidal despair. She wishes that the consequences weren’t so harsh - as other addicts do. Mate argues that self-accusation is a relentless whip that spurs so many perfectionists to buckle down, do more, be better. It needs to be seen for what it is - a callow voice that needs to be firmly, but quietly put in its place.

Nan and Brian in Bed, New York City, 1983

More recently, (in addition to dealing with her own addiction) Goldin has engaged in personal and collective activism against Purdue Pharma, manufacturers of the opioid OxyContin which has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. Purdue marketed the product as being a less addictive opioid than other painkillers, whilst suppressing evidence to the contrary.

Her particular targets in this campaign has been the Sackler family, who control Purdue, and her fame as an artist gave her a platform to raise the banner. The Sacklers have promoted themselves as benevolent art philanthropists among other things, but Goldin was appalled at their callousness and inhumanity. As a result of her campaigning, some of the world’s most prestigious galleries, including the Met in New York, no longer accept money from the Sacklers and have removed their logo from their buildings.

Tough Sharon

When Mate asked her about her activism, Goldin responded “you need something bigger than yourself.” In her case, it was the suffering of others, a situation she could rectify and which helps her to stay sober. Mate believes that in standing up to a toxic culture, Goldin found herself.

Hello, my name is Geoff. You may be interested to know that I’m a fulltime artist these days and regularly exhibit my work in Victoria, but particularly in Melbourne. You may wish to check out my work using the following link; https://geoffharrisonarts.com

References;

“The Myth of Normal”, Gabor Mate, 2022

“The Lonely City”, Olivia Laing, 2016